Van Honthorst’s The Concert – singing together or perhaps a peregrination of the prodigal son?

The Concert (Theft of the Amulet), Gerrit (Gerard) van Honthorst, Galleria Borghese

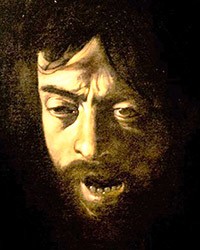

The Concert (Theft of the Amulet), fragment, Gerrit (Gerard) van Honthorst, Galleria Borghese

Gerrit (Gerard) van Honthorst, The Concert (Theft of the Amulet), fragment, Galleria Borghese

Gerrit (Gerard) van Honthorst, The Concert (Theft of the Amulet), Galleria Borghese

The Concert (Theft of the Amulet), fragment, Gerrit (Gerard) van Honthorst, Galleria Borghese

The Concert (Theft of the Amulet), Gerrit (Gerard) van Honthorst, Galleria Borghese

What a beautiful, bright scene, in which the painter plays with our sense of vision, our naiveté, and our knowledge of human nature, perhaps wanting to tell us that what we see is not exactly what is. And what do we see? A group of people singing accompanied by a cello. A young woman is leaning over the table delicately touching the ear of a seated singer. An older woman behind them seems to be playing the role of a chaperon, extending her finger as if she had wanted to warn the young couple against excessive familiarity, while the musician carefully observes the entire company.

What a beautiful, bright scene, in which the painter plays with our sense of vision, our naiveté, and our knowledge of human nature, perhaps wanting to tell us that what we see is not exactly what is. And what do we see? A group of people singing accompanied by a cello. A young woman is leaning over the table delicately touching the ear of a seated singer. An older woman behind them seems to be playing the role of a chaperon, extending her finger as if she had wanted to warn the young couple against excessive familiarity, while the musician carefully observes the entire company.

This outstanding painting of a Dutch artist, who had studied in Rome for several years, gaining renown as an author of compositions deeply immersed in darkness, shows him in a completely new light. In the summer of 1620 van Honthorst returned to Utrecht covered in fame, receiving a grand welcome from the artistic and intellectual elite of the city. He was thirty years old and quickly became a respected citizen, a member, and later the dean of the Utrecht-based Guild of St. Luke. In time he also gained renown as a painter who in his workshop employed approximately twenty-five aides, as was stated by Peter Paul Rubens who visited him in 1627. This should come as no surprise – as a fertile and popular painter, he had to deal with a countless number of commissions: for religious paintings, but above all genre scenes and portraits. In Utrecht Honthorst brightened up his pallet, did away with the strong chiaroscuro, and placing torches and candles in his paintings, which is what he became famous for in Rome, although he did use them occasionally since they were perfect for arranging religious scenes.

However, he completed paintings that were mainly destined to adorn the residences of wealthy townsmen and petty nobility, who had desired scenes that would please the eye in the interiors of their homes. Concerts and merry company at the table were topics that were perfect in this situation, and in addition, they contained (or may have contained) a certain moralistic or allegoric message. Such a painting, therefore, forced the onlookers to interpret and often stimulated discussions. These popular at that time representations could have been an antidote for the crisis-filled Utrecht of the twenties of the seventeenth century – a city that was completely different than the one the painter had left ten years prior – beset with fear, war, conscription, and an epidemic, as well as intolerance. Its Protestant authorities forbade playing music, not only in taverns but also in private homes, organizing lavish feasts with excessive drinking, gambling, and jesting, as well as contacts between unmarried women and bachelors. An atmosphere of Puritan terror filled the city. How then, does one paint a merry company and not face dire consequences?

This time the painter drew from the experience of young Caravaggio, whose work he diligently studied during the years he had spent in the city on the Tiber. Where is this inspiration visible at first glance? The beams of light illuminating the background of the painting are similar to those appearing in early works of Merisi, and when we look closely upon the tray with fruit, in it we will notice the echo of his magnificent still nature, with one noticeable difference. While in the works of Caravaggio the fruits are always overripe and shriveled (Boy with a Basket of Fruit, Basket of Fruit), those shown by van Honthorst seem fresh. And the elderly woman in a turban, on the right side – is she not reminiscent of those, who were often painted by Caravaggio (Judith with the Head of Holofernes)? The role of this woman is also the key to understanding the concept of the painter’s work, which may only seem to be a scene of merrymaking. And here, once again we can see the influence of Caravaggio – an author of ambiguous works, often with multiple meanings. What do we really see upon the painting? Let us look once again. The young woman who is holding a songbook in one hand and with the other brushes the face of a youth, or perhaps she is taking a pearl-filled jewel off his ear. Upon seeing this, the crone in the background cannot hold back her laughter. Soon she will probably take the valuable prize off the young girl's hands as she is most likely in on her plan, similar to the alert cello player ready to help (if needed). The knife found immediately next to the youth's hand, is just like a gun hanging on a wall in Hollywood motion pictures, which may at some point go off, but does not have to. Van Honthorst was most likely familiar with Caravaggio's The Fortune Teller – a perverse tale of the illusion of seeing and the dangers of a young age: the Gypsy woman depicted in the painting gently touches the youth's hand, while we focus on this erotic gesture do not see that at the same time she is removing a ring from his finger. Similarly in van Honthorst's work – the chaperon may be a procuress, the woman-in-love a thief, while the hired singer may be an accomplice of both women, but perhaps not – that depends on the person who is looking. Are the people in the painting making music with a group of friends, or is it a scene taking place in a house of ill repute? Van Honthorst painted many such scenes in the brothels of Rome, for example, Merry Company with a Lute Player (1619, Galleria degli Uffizi). In these compositions, the main roles were played by youths, beautiful young prostitutes with deep cleavage, and old procuresses. Wine, music, and singing were inherent elements of such meetings, while the atmosphere was relaxed and filled with eroticism. However, here the woman's cleavage is almost completely covered by the youth's head. The wine jug is far away, while the chalice contains water. There is also no trace of feasting. Therefore, here we are dealing with camouflage, created in the name of Protestant puritanism, that significantly concealed the context of the painting. This was especially true because the seen referenced an important figure from the New Testament – the prodigal son "who squandered his wealth in wild living" (Lk 15: 11-32). And thus, from a morally ambiguous scene, a moralistic scene came to be.

And perhaps it was the artist himself playing the role of the prodigal son as he spoke of his Roman experiences. Recently it was revealed that immediately prior to returning to Utrecht van Honthorst was arrested in the company of a prostitute with whom – as was reported by the police – he had maintained close relations for many months.

The painting is found in the Galleria Borghese, however, it was not its founder, Scipione Borghese, who nonetheless greatly valued van Honthorst, who bought the painting for the collection. This did not occur until 1770 at an auction of the artist’s works organized in Amsterdam by his family. The inventory includes a title Theft of the Amulet, which clearly shows the intentions of the painter, although the painting is known by a rather euphemistic title The Concert.

The Concert (Theft of the Amulet), Gerrit (Gerard) van Honthorst, 1626–1630, oil on canvas, 168 x 202 cm, Galleria Borghese

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !